I have been following Yeats’s method, experimenting with automatic-speech with my wife. I decided to approach one automatic-speech experiment as if it is an art interview, where I would ask the ‘communicator’ questions. The questions and answers were made into the film Interview with authorial-Self (2007; ![]()

![]() see also revised transcript

see also revised transcript ![]() ). Yet, I noted one difference from Yeats’s description. Yeats (1974: 8) quotes his ‘communicators’ as saying, ‘We have come to give you metaphors for poetry’ whereas my experience with my ‘communicator’ revealed that he is a part of my own self, my own creative self, hence he defined himself not as a ‘communicator’ but as my ‘authorial-Self’. For this reason I have re-enacted the answers that were given to me by authorial-Self through my wife’s channelling, and using the computer I split the screen to include both ‘Gils’ – Gil who asks the questions on the left, and Gil the authorial-Self on the right (fig. 12).

). Yet, I noted one difference from Yeats’s description. Yeats (1974: 8) quotes his ‘communicators’ as saying, ‘We have come to give you metaphors for poetry’ whereas my experience with my ‘communicator’ revealed that he is a part of my own self, my own creative self, hence he defined himself not as a ‘communicator’ but as my ‘authorial-Self’. For this reason I have re-enacted the answers that were given to me by authorial-Self through my wife’s channelling, and using the computer I split the screen to include both ‘Gils’ – Gil who asks the questions on the left, and Gil the authorial-Self on the right (fig. 12).

In this way, I would suggest, drawing inwards can be said to allow the artist to open up to his or her own higher creative self. The idea of interacting with oneself is used widely in art, for example, in Gwen Stefani’s music video clip What You Waiting For? (2004), which deals with ways in which the artist becomes inspired to create art by acknowledging the inner self (fig. 13).

[Figure 13 – awaiting permission to include image here.]

Figure 13: Still image from Gwen Stefani’s video clip What You Waiting For? (2004). Image © Universal Music Publishing Ltd.

Artist Marcel Duchamp explains his invented alter-ego figure, Rrose Sélavy (1920s): ‘…not to change my identity, but to have two identities’ (From the display caption, Tate Modern, London, March 2008.) And the poet Shelley, according to Ackroyd (2006), described a vision in which he saw an image of himself walking towards him and asking, ‘how long do you mean to be content?’ In my case the opposite happened as I was the one to ask my ‘image’ questions.

The sense that the inner voice can exhibit itself as part of the artist can be illustrated with the creative process of painter Barry Stevens. Stevens (![]()

![]() para. 33) explains, ‘External and internal are for me like a spectrum or a continuum. The point at which one becomes the other is arbitrary’. Blake’s claim that ‘the human might… be linked to the divine’ (Beer, 2003: xii) is seen by Stevens not just as a link in which one point touches another, but rather as a continuum, a spectrum. This spectrum suggests that artists are connected to their inner voice, or source of creative energy, at all times, but at specific moments they acknowledge it, or open to it, and allow for the creative flow.

para. 33) explains, ‘External and internal are for me like a spectrum or a continuum. The point at which one becomes the other is arbitrary’. Blake’s claim that ‘the human might… be linked to the divine’ (Beer, 2003: xii) is seen by Stevens not just as a link in which one point touches another, but rather as a continuum, a spectrum. This spectrum suggests that artists are connected to their inner voice, or source of creative energy, at all times, but at specific moments they acknowledge it, or open to it, and allow for the creative flow.

If we agree that the artist is connected at all times to the creative source, we might ask whether each artist is connected to a so-called individual source, or whether they are connected to a collective or shared source, from which all draw. Poet Anne Stevenson (![]()

![]() para. 27) asserts that ‘…poetry is literally untranslatable. However… you can transfer the spirit of it from one language to another’. Stevenson reveals that there is a core essence, which she defines as spirit, which can be exhibited within all cultures, even when the language is non-transferable. Poet Maggie Sawkins suggests that this core essence can reveal itself not by being translated or transferred, but rather by splitting itself, as it seems, and presenting itself to people from different places. She (

para. 27) asserts that ‘…poetry is literally untranslatable. However… you can transfer the spirit of it from one language to another’. Stevenson reveals that there is a core essence, which she defines as spirit, which can be exhibited within all cultures, even when the language is non-transferable. Poet Maggie Sawkins suggests that this core essence can reveal itself not by being translated or transferred, but rather by splitting itself, as it seems, and presenting itself to people from different places. She (![]()

![]() para. 15) says: ‘You could dream similar dreams to someone who lives in Africa, even if you are from a completely different culture’.

para. 15) says: ‘You could dream similar dreams to someone who lives in Africa, even if you are from a completely different culture’.

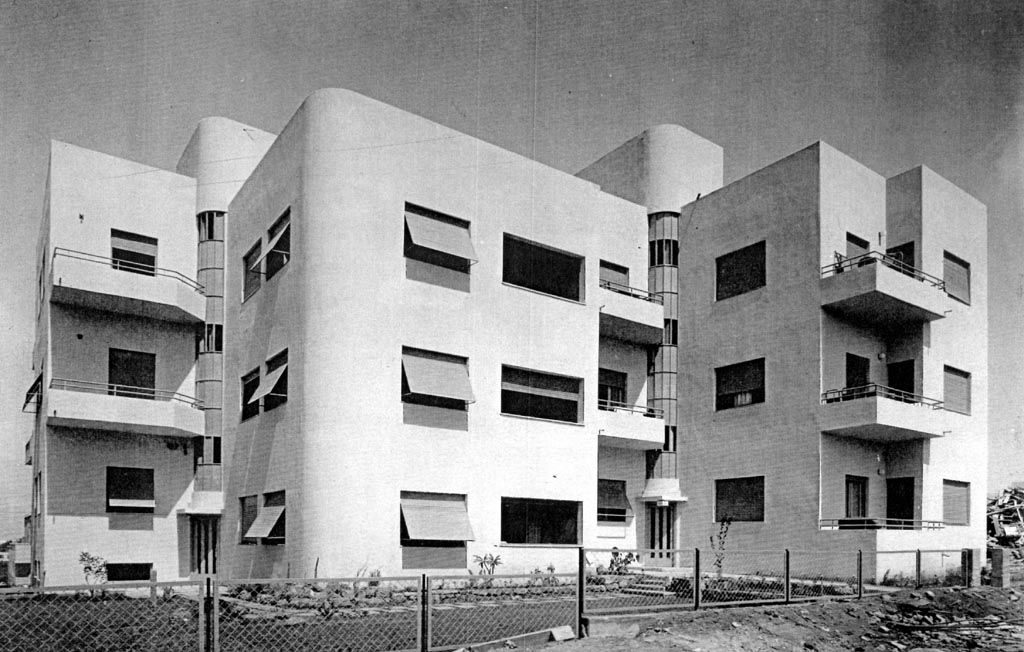

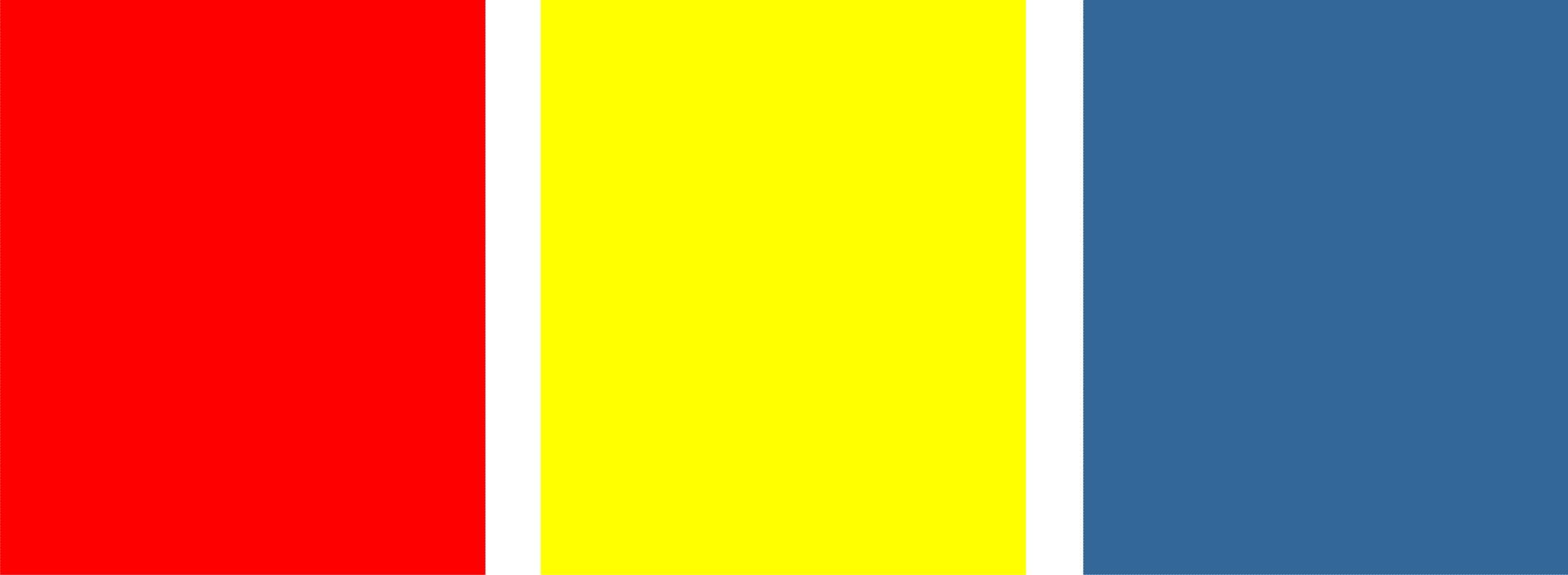

Shared ideologies that inspire simultaneously different art movements can be seen through art works. For example, the German Bauhaus and the Russian Constructivism movement, were operating in the early 20th century at a great distance from each other, yet they shared similar ideologies. The Bauhaus’s social ideology of using functional and simple shapes covered with a single colour (Aynsley, 2001: 61) (fig. 14) were also inspiring the Russian Alexander Rodchenko’s social ideology of functionality and use of single colour and simple shapes (Dabrowski, 1998: 57) (fig. 15). The Bauhaus applied this ideology in architecture, and Rodchenko in painting.

Figure 14: A Bauhaus style building as part of ‘White Tel-Aviv’ (1933). Architect: Yitzhak Rapaport. Image in public domain.

Figure 15: Illustration (by Gil Dekel) of Rodchenko’s Pure Red Colour, Pure Yellow Colour, and Pure Blue Colour (1921, oil on canvas, each panel, 62.5 x 52.5 cm.) Original work in Moscow, A. Rodchenko and V. Stepanova Archive.