Like word, image is a representative tool used by people to understand reality. More so, it is natural for people to think that what they see represents things as they truly are, asserting the famous dogmatic view: ‘I will believe it when I see it’. Yet, Morris (1989: 339) reminds us that just like words, images are also representational signs, implying that images are indicating different things than the observed. Alan Corkish (![]()

![]() para. 23) reveals how this may happen, saying that ‘…photographs often capture unexpected pointers or markers to other things’. By capturing the ‘unexpected’ images come to serve as ‘…markers to other things’. Yet, the ‘unexpected’ does not suggest that a thing was not there to begin with, but rather that a person did not expect or did not pay attention to it. By not expecting, the observer may overlook it. The presence of visible things may only be noticed later, in the example of Corkish, by looking at it again in a photograph.

para. 23) reveals how this may happen, saying that ‘…photographs often capture unexpected pointers or markers to other things’. By capturing the ‘unexpected’ images come to serve as ‘…markers to other things’. Yet, the ‘unexpected’ does not suggest that a thing was not there to begin with, but rather that a person did not expect or did not pay attention to it. By not expecting, the observer may overlook it. The presence of visible things may only be noticed later, in the example of Corkish, by looking at it again in a photograph.

Installation artist David Johnson (![]()

![]() para. 40) asserts that while things might be ignored, still they are registered and remain, as he says, ‘…in the back of my mind…’ In that respect even when not consciously noticing things, still they are captured and registered. Jung is well known for his research on the images that are registered in one’s unconscious, ‘absorbed subliminally’ as he (1972: 23) puts it. Yet, Jung also has an important theory regarding the conscious mind and the way that it seemingly ignores things. He (1963: 184) argues that the act of ignoring happens after the conscious mind has allowed images to rise. As the images rise, we ‘…wonder about them a little,’ and we then neglect them, not trying to understand them. According to Jung, images are fully present in the thinking aware mind, and are not ignored but rather neglected.

para. 40) asserts that while things might be ignored, still they are registered and remain, as he says, ‘…in the back of my mind…’ In that respect even when not consciously noticing things, still they are captured and registered. Jung is well known for his research on the images that are registered in one’s unconscious, ‘absorbed subliminally’ as he (1972: 23) puts it. Yet, Jung also has an important theory regarding the conscious mind and the way that it seemingly ignores things. He (1963: 184) argues that the act of ignoring happens after the conscious mind has allowed images to rise. As the images rise, we ‘…wonder about them a little,’ and we then neglect them, not trying to understand them. According to Jung, images are fully present in the thinking aware mind, and are not ignored but rather neglected.

This suggests that the act of neglecting images is an act where the conscious mind represses images back to the unconscious. Paskin’s (![]()

![]() para. 6) argument that she feels as if working ‘…from a place that you might not have such an easy access to,’ can assert that images do rise up to the working consciousness but are later repressed, leaving the artist with a feeling that she is fully in the creative work and yet unaware to its rising content. In that way the conscious mind manages to capture images coming from the senses and then repress them, which I will term ‘repressivism’. Repressivism does not refer to those images repressed in the unconscious. Rather repressivism refers to the act of the conscious mind to contemplate images, to repress them, and to give us the illusion that images bypassed the conscious mind and were directly repressed in the unconscious.

para. 6) argument that she feels as if working ‘…from a place that you might not have such an easy access to,’ can assert that images do rise up to the working consciousness but are later repressed, leaving the artist with a feeling that she is fully in the creative work and yet unaware to its rising content. In that way the conscious mind manages to capture images coming from the senses and then repress them, which I will term ‘repressivism’. Repressivism does not refer to those images repressed in the unconscious. Rather repressivism refers to the act of the conscious mind to contemplate images, to repress them, and to give us the illusion that images bypassed the conscious mind and were directly repressed in the unconscious.

If we accept this assumption, we should then consider whether there is enough research that examines this process. Many authors, such as Alma, Wyllie & Ramer (2002: 65) in their important study on developing creativity, suggest forms of creativity, or intuition as they see it, as productive forms that bypass the conscious mind and that we should learn to connect to. While these studies are important for informing the creative powers that are not subjected to conscious or logic, it is also important to note the counter-creative power of the conscious mind to produce blocks. Such blocks seem to leave the artists with the feeling of knowing things and yet not being fully aware of them. David Johnson (![]()

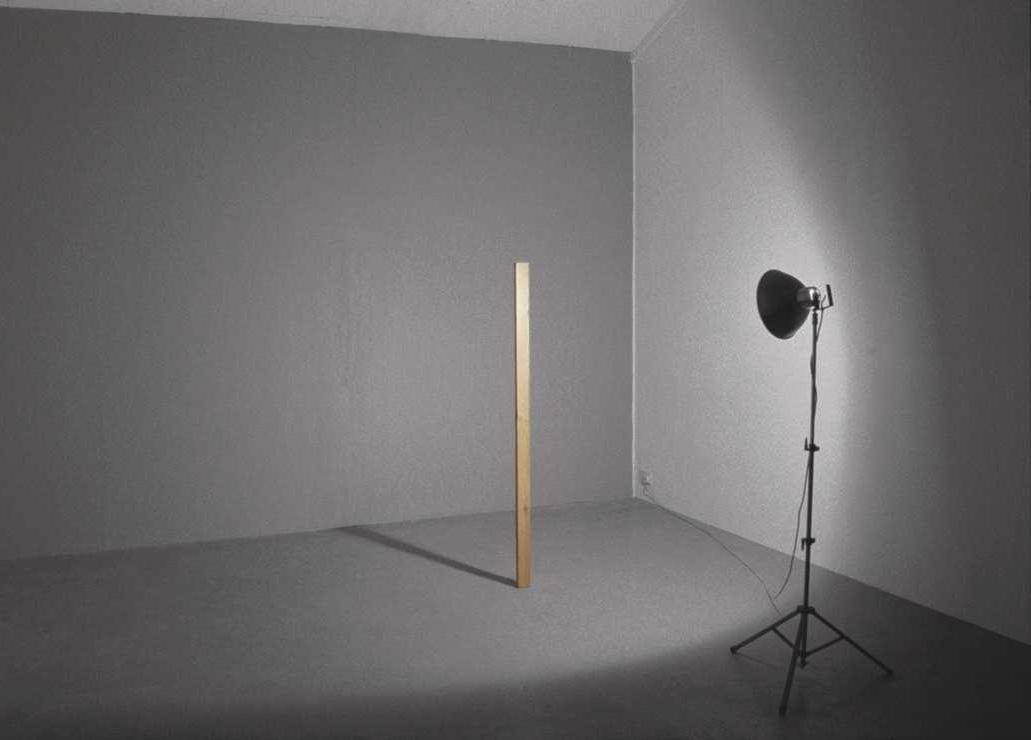

![]() para. 18) deals with this duality, trying to illustrate it in his works, ‘…something that you could not see yet is the centre of the work… things you cannot see but know about, therefore affect the way you see: the non-visible’. In his work Trying to Imagine Not Being (2003) he painted out the shadow that a post casts on a wall. The shadow is noticeable on the floor, running to the wall – but does not exist on the wall where it should be (fig. 41).

para. 18) deals with this duality, trying to illustrate it in his works, ‘…something that you could not see yet is the centre of the work… things you cannot see but know about, therefore affect the way you see: the non-visible’. In his work Trying to Imagine Not Being (2003) he painted out the shadow that a post casts on a wall. The shadow is noticeable on the floor, running to the wall – but does not exist on the wall where it should be (fig. 41).

Figure 41: David Johnson, Trying to Imagine Not Being (2003, floodlight, post, emulsion paint, black wall painted so shadow disappeared, variable dimensions.) Image © the artist. Permission to use image obtained from the artist.

Casting one’s own shadow on the same part of the wall reveals what Johnson (para. 9) calls a ‘white ghost’ (fig. 42).

Figure 42: David Johnson, Trying to Imagine Not Being (2003, floodlight, post, emulsion paint, black wall painted so shadow disappeared, variable dimensions.) Image © the artist. Permission to use image obtained from the artist.

Image, I would say, is a symbol used by artists to denote something else, something which we cannot see. Even poetry, whose main tool is words, ‘…does use images to try to convey abstract thoughts and feelings…’ (Maggie Sawkins ![]()

![]() para. 17). The way in which artists approach the invisible and the abstract is explained by the Constructivist Naum Gabo (Annely Juda Fine Art, 2003: [4]). Gabo says, ‘Artists do not observe the world, but live the world’. Gabo asserts that artists do not look at reality in the common sense, but rather have a different mode of absorption of images – the ‘living’ in the world; the experiencing of it.

para. 17). The way in which artists approach the invisible and the abstract is explained by the Constructivist Naum Gabo (Annely Juda Fine Art, 2003: [4]). Gabo says, ‘Artists do not observe the world, but live the world’. Gabo asserts that artists do not look at reality in the common sense, but rather have a different mode of absorption of images – the ‘living’ in the world; the experiencing of it.