The artistic experiences that I examined are manifested from the inner reality and to the external environment through shapes and colours.

Kandinsky, in his study Point And Line To Plane (1979) explains that abstract forms are isolated from their objective environment of material and plane (p. 21). This isolation means that the abstract form frees itself, as Kandinsky (p. 28) asserts, from dependency or practical use, beginning ‘its life as an independent being’. Kandinsky’s assertion indicates an inner quality that the artist observes in the abstract shapes.

Artist and architect Victor Pasmore (Bickers & Wilson, 2007: 352) explains that shapes are not only representative but inherent in the way that people observe reality. Shapes that are observed in nature, such as the circle or the square, do not just exist in nature, but rather they represent some basic form of a visual sensation within people, Pasmore explains. These visual sensations are explored by artists through abstract forms that are not representative but rather stand as an expression of the language of forms themselves.

Abstract / Light / White

Bolt (2004: 11) asserts the importance of abstract forms, indicating the misleading prevailing assumption by art theorists and historians that still seem to assume that visual art is representational. Digital artist Renata Spiazzi (Nalven, 2005: 155) adds, ‘Too often, people looking at a painting get sidetracked by the subject and never get to the real beauty of the work’. Abstraction, according to Spiazzi, allows one to focus on the beauty of the medium itself.

The use of abstract shapes in works of art allows artists freedom and flexibility to remain adaptive to changing inner ideas and emotions, which resonates with the unfixed forms of the shapes. Abstract forms maintain a dialogue with the emotions, continuing to evolve and to be clarified as the artist clarifies his or her own ideas. Abstract forms help the artist to discover his or her own inspired-inner-self, as it may be called, without the need for expertise or technical perfection. The artist may well be proficient in the skill of art making, as Picasso has demonstrated from a very early age, yet the skill is not seen as a necessary criteria for the expression in abstract art. I feel this can be demonstrated in the works of the Supermatist Malevich.

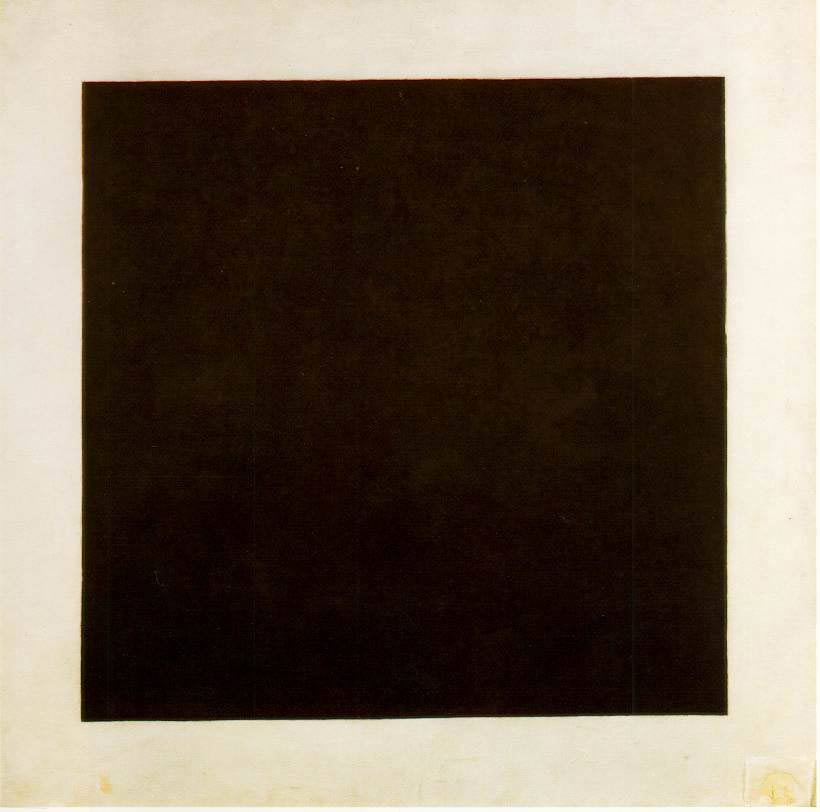

In his attempt to express a universally shared feeling, Malevich (Drutt, 2003) asserted that pure geometrical forms have no specific cultural element to them and as such they can be universally comprehended regardless of cultural or ethnic origin. A simple black square, Malevich asserts, represented economy, which he saw as the most important motif or quality through which to examine reality (Drutt, 2003: 33) (fig. 52).

Figure 52: Kazimir Malevich, Black Square (1923, oil on Canvas.) St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum. Image in public domain.

The search for an abstract and a non-objective in his works, was seen by Malevich (Drutt, 2003: 61) as ‘the optimism of a nonobjectivist’. This optimism is well discussed by Gabo through his own abstract construction works, yet he sees it from a different perspective. While Malevich was reaching to reduce art to zero and then go beyond the zero (Drutt, 2003: 46), Gabo was looking for abstract art that retains the laws of nature (Bickers & Wilson, 2007: 37). Gabo’s use of abstract forms was not meant to reach for anti-art, a negation of form, but rather to explore forms and space without depicting mass. He (Bickers & Wilson, 2007: 35) asserts, ‘my art is optimistic, because it looks forward and has a vision’. I draw from this that the symbolic image of ‘looking forward’ is adequate to Gabo’s idea of abstract spaces with no mass, where no specific image is defined but rather multiple possibilities exist for one to look at.

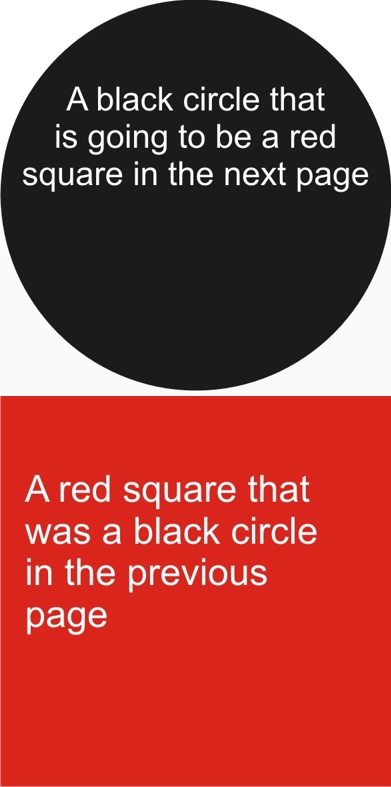

In that same spirit I have attempted to capture the space of artistic possibilities that contains no mass, in my work A Black Circle That is Going To Be (2008) (fig. 53).

Figure 53: A Black Circle That is Going To Be (2008, electronic Flash animation on www.poeticmind.co.uk). Image © Gil Dekel.

The work was created as an online Flash animation, where the viewer first sees the black circle with its text message of ‘going to be a red square in the next page,’ and after five seconds the circle disappears and the red square appears, with its text message asserting it is ‘a red square that was a black circle in the previous page’. The work is accompanied with this assertion:

‘What interests me is not the square or the circle, but what is in between the two: the artistic process by which one becomes the other.’

In this work I have attempted to bind the abstract space of the creative process between two covers, like a book bound inside covers – the black circle as a front cover, and a red square as its back cover. By linking the two parts I attempted to link the idea of what is going to be created with the actual artwork. This work represents the ‘covers’ of a creative process, which hold the empty space in which creativity occurs. Yet, the creative space between the covers exists only thanks to the text on the images, which asserts this space. The text is read by the viewer, and in that respect the viewer creates that abstract space in his or her mind. The work serves as a frame for a creative process that occurs in the mind of the viewer.