Painter Felice Varini also uses the observation of the viewer as part of constructing his works. In his works he paints geometrical shapes on urban landscapes, using the perspective-localised method in which the complete shape of the work is noticed only from one focal point (fig. 54). Looking from outside the vantage point, the viewer sees fragments, the broken shapes (see two examples in fig. 55).

Figure 54: Felice Varini, Three Ellipses For Three Locks (2007, acrylic paint, seen from the vantage point). Image © the artist. Permission to use obtained from the artist.

Figure 55: Felice Varini, Three Ellipses For Three Locks (two views) (2007, acrylic paint, seen from outside the vantage point). Image © the artist. Permission to use obtained from the artist.

Unlike my work where the work enters the mind of the viewer, in Felice’s work the viewer walks around the painting, trying to construct an image from different points. Elements in the work are observed through the process of viewers walking around it. Felice (![]()

![]() para. 12) explains:

para. 12) explains:

‘My concern is what happens outside the vantage point of view. Where is the painting then? Where is the painter? The painter is obviously out of the work, and so the painting is alone and totally abstract, made of many shapes. The painting exists as a whole, with its complete shape as well as the fragments.’

In that respect Felice has brought the artistic search for abstract shapes from the invisible and non-existence back to the physical reality. The physical reality serves as the element, or the surface, that produces abstract shapes, in what Felice (![]()

![]() para. 31) suggests is a step forward in the history of abstract art:

para. 31) suggests is a step forward in the history of abstract art:

‘The question that I am asking as an artist is, ‘What is the next step in the history of art after Mondrian, Malevich and Pollock? What can we offer today that will take us to the next step in abstract painting?’ My answer is to work on the three-dimensional reality…’

Installation artist David Johnson seems to take abstract art further by trying to create an experience in which abstract forms are created, and then removed, in what can be termed ‘the abstraction of abstract art’. In The Invention of Nothingness (2008, work in progress) he painted a black abstract form on a wall which covers the shades of the light which is cast on that wall from a floodlight. Once the floodlight is turned off, the viewer can see the abstract black form on the wall (fig. 56).

Figure 56: David Johnson, The Invention of Nothingness (2008, work in progress, floodlight off, emulsion paint.) Image © the artist. Permission to use image obtained from the artist.

But once the floodlight is turned on, the light with its brightness covers the black form, so that the viewer sees a uniform wall hue (fig. 57).

Figure 57: David Johnson, The Invention of Nothingness (2008, work in progress, floodlight on, emulsion paint.) Image © the artist. Permission to use image obtained from the artist.

In that way, Johnson has turned the qualities of abstract shapes upside down or inside out. Abstract forms are not created by light, but rather are negated by light. Johnson has demonstrated an attempt to create abstract forms by ‘flushing’ or rendering images with light.

While Johnson uses light to create a negation of shapes, artist Katayoun Dowlatshahi captures light directly onto glass surfaces, hence using light as the brush (fig. 58). She (![]()

![]() para. 7) explains:

para. 7) explains:

‘…the light source can be represented as a mirror; by shattering that mirror many individual fragments or shards are created. You and I and all other beings are represented by these individual fragments. However, we reflect that one light source from many different perspectives; that is what makes us all unique.’

Figure 58: Katayoun Dowlatshahi, Drawing Fragments of Light I, II & III (2004, triptych, gelatine, blue & black pigment onto glass, 168 x76 cm each.) Image © the artist. Permission to use image obtained from the artist.

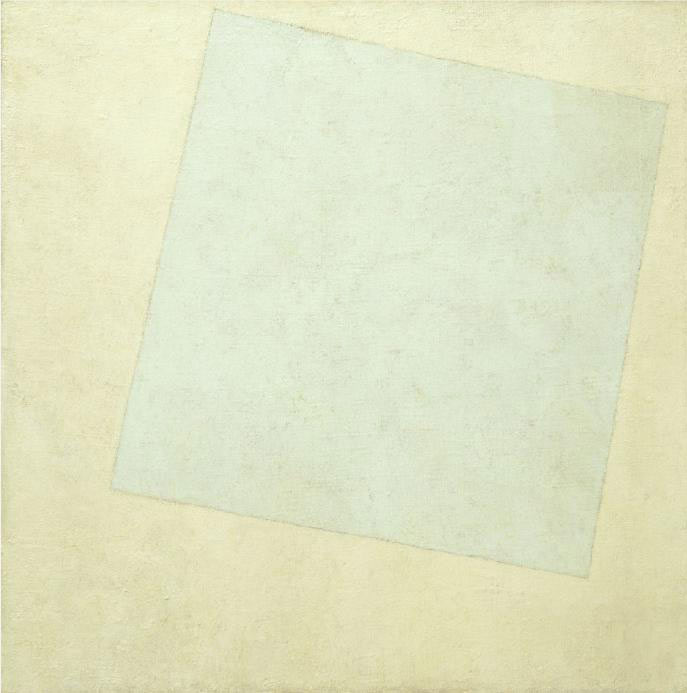

The use of light and light colours is not new. Following Kirchner’s advice that colours’ ‘birth’ is from light and their combination makes white (Grisebach, 1999: 185), artists have been attempting to remove the sense of ‘shapeness’ of forms by ‘flooding’ them with bright colours, usually with white. Malevich’s White on White from 1917 is an example (fig. 59). However, I observe that rendering shapes with bright colour is not meant only for the purpose of abstraction or negation of image, but also for the purpose of creating a sense of expansion. Ambrose & Harris (2005: 142) explain that rendering a shape with bright colours will give the impression that the shape is larger than a similar shape rendered with dark colours. Light colours have the property to produce an impression of expansion. Malevich is known for his use of white colours for representation of aesthetics that will lead to what he sees as a spiritual freedom. White colour, with its quality of expansion, carries an essence of infinity and higher feelings in his works (Lowry, 2004: 85).

Figure 59: Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918, oil on canvas, 79.4 x 79.4 cm.) New York, Museum of Modern Art. Image in public domain.

I consider Malevich’s attempt to convey the pure, or the spiritual as he sees it, as unique in that he produced a white colour layer applied on another white colour layer. However, we must admit that Malevich’s work is hung on the gallery’s wall, and in that respect the work, with its light hue, can be seen only thanks to the different hues of the gallery’s wall, which might even be dark.